- Home

- John Robin Jenkins

Poverty Castle

Poverty Castle Read online

POVERTY CASTLE

John Robin Jenkins was born in 1912, one of four children, in the village of Flemington, near Cambuslang. He studied English at the University of Glasgow. When World War II broke out, he registered as a conscientious objector and was directed to work for the Forestry Commission; he used this experience in the acclaimed novel, The Cone-gatherers. In 1957 he moved abroad to work in Spain, Afghanistan and Malaysia. In 1968, he settled in Dunoon where he remained for the rest of his life. In 2002 he received the Saltire Society’s Award for Lifetime Achievement. He died in 2005.

Alan Warner was nominated by Granta magazine in 2003 as one of the Twenty Best of Young British Novelists. He is the author of five novels: Morvern Callar (1995); These Demented Lands (1997); The Sopranos (1998); The Man Who Walks (2002); and The Worms Can Carry Me to Heaven (2006).

Other titles by Robin Jenkins

Dust on the Paw

Leila

Love is a Fervent Fire

Lunderston Tales

Matthew & Sheila

The Missionaries

The Pearl-fishers

Sardana Dancers

Some Kind of Grace

The Thistle and the Grail

A Very Scotch Affair

Willie Hogg

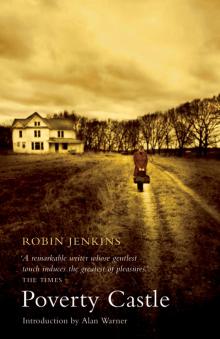

ROBIN JENKINS

Poverty Castle

This ebook edition published in 2011 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 1991 by Balnain Books

This edition published in 2007 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © the estate of Robin Jenkins, 1991

Introduction copyright © Alan Warner, 2007

The moral right of Robin Jenkins to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by his estate in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ebook ISBN: 978-0-85790-160-6

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Part Two

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Part Three

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

For Alison, Trisha and Emma, my grand-daughters

Introduction

I AM AFRAID I do not enjoy novel introductions which, in analysing the work, haplessly reveal every plot and character detail, so I wish to beg indulgence and state personally what the work of Robin Jenkins has meant to me.

The first Robin Jenkins novel I ever read was The Cone-gatherers. When that beautiful and ominous parable, first published in 1955, was brought back into print by a London publisher, containing a new introduction by Iain Crichton Smith, I was a seventeen-year-old in Oban. It was 1981 or maybe 1982. Though a recent reader of Penguin Classics and of science fiction, I then held the curious teenage assumption that living novelists simply did not exist in contemporary Scotland. For me, isolated below the mountains of Argyll, living Scottish writers were something that must surely have vanished from our modern society, like tuberculosis or railway steam engines. I had no excuse for my ignorance. I attended high school, my family was affluent, we owned two colour televisions and we subscribed to newspapers. Not that there was much about Scottish novelists on television or in the papers then. Today I blame the antiquarian tastes of Sir Walter Scott, whose tomes were so very well represented in our local tourist-orientated newsagent. For an impatient teenager, the cult of Sir Walter added to that ambience of Scottish novels being in some way situated in the past, irrelevant and all ‘’tis so-many years since . . .’.

I can still recall the absolute physical shock of spotting Alasdair Gray’s Lanark in hardback edition, swirling in the necromancy of its own austere artwork. Here was a remarkable new novel by a living Scot! Equally awakening though, was that introduction to The Cone-gatherers, for at the very bottom of the page, it was signed off ‘Iain Crichton Smith. Oban’.

I had to face up to it and grant corporeal existence to contemporary writers not only in Scotland but stomping my very own Argyllshire turf. Suddenly I was rooting out the works of those Scottish authors on day visits to second-hand book (and record) shops in Glasgow. Sometime soon after, I shyly approached Iain Crichton Smith himself on the Glasgow train as it rolled down the Pass of Brander. He was patient and kindly as he listened to nervous ramblings about my then university-less status and my dodgy ambitions to write. I showed off about my latest reading: the poems of Edwin Morgan and W. S. Graham, novels of Fionn MacColla, George Friel and of course Robin Jenkins’ The Cone-gatherers. I recall after our enthusing about these works, Iain very generously wrote down his own as well as Edwin Morgan’s home addresses. He also gave me Robin Jenkins’ address, in South Cowal, close to Dunoon. I soon exchanged letters with Iain and eventually with Edwin Morgan. Today – however presumptuous on my own part – I very much regret that I never wrote to Robin Jenkins, to say thank you.

*

In 1984 I had taken off for college to a London in the clutches of Thatcherism; the miners’ strike collection buckets rattling outside tube stations. For those first months in London, I often awoke with the lush summer hills of home going out like blown light bulbs in my mind. Choked with a pathetic nostalgia, my pathological homesickness shocked and embarrassed me. As a palliative, I now recognise, I devoured Scottish literature, ordered through Ealing Central Library which was situated in the midst of a new shopping mall. I remember reading Gray, Owens and Kelman’s anthology Lean Tales which was a revelation to me. But I also read Robin Jenkins’ The Awakening of George Darroch, which had just been published, as well as Jenkins’ older novels which were much more difficult for the librarians to track down in far-flung home-county branches: The Thistle and the Grail, Dust on the Paw, A Would-be Saint and Fergus Lamont. At that time I also read Iain Crichton Smith’s latest (now out-of-print) novels, The Tenement – set in a mildly disguised Oban – and The Search.

I myself was searching then: what was this country of mine called Scotland?; who were its artists?; and where, if at all, could I ever fit in? I am not trying to flatter myself that Jenkins’ novels eventually influenced my own future novels – in fact my generation of Scottish novelists could be seen as rea

cting savagely against both Jenkins’ understated style and his urbane approach. But those Robin Jenkins’ novels which I read back then very literally sustained me and allowed myself at least the illusion that, homesick in the midst of London, I was part of a culture to the north. I was lucky to have read them at that time which was a crossroads for so much.

*

How I groan today when I read reactionary Scottish critics – our very own unelected Town Councillors of Literature – determined to insert the knife into the recent efflorescence of Scottish literary activity. Do these critics actually remember the Scottish bookshelves in 1980–82? It was then that the historian Christopher Harvie, in No Gods and Precious Few Heroes, had understandably pondered: ‘Perhaps the (Scottish) novel was dying and there were other ways of analysing the Scots predicament?’ I do remember the bookshelves then. For the reader of current Scottish novels it was a grim and dull lull before the relief of a great storm. Note how it was in the second-hand book shops, like an archaeologist, I had unearthed more recent Scottish literature. Until the liberating arrival of Alasdair Gray and James Kelman, this was a time when the Scottish fiction section of John Smith’s in Glasgow contained most of the works of Sir Walter Scott, of Baron Tweedsmuir (John Buchan), of Sir Compton Mackenzie (including all The Four Winds of Love) and most of Dame Muriel Spark. These works are part of Scotland’s culture but often there were simply no other novels – especially more recent ones. Even the Scottish novelists of the 1960s and 1970s, like Robin Jenkins, James Kennaway, Elspeth Davie, Gordon Williams and Alan Sharp, were very difficult to find, their books going through a semi-permanent black spot with regard to being in print; though Kennaway was soon handsomely reprinted but to resounding indifference. At that time Scotland lacked dynamic publishers which, thankfully, it now has. Back then contemporary Scottish novels seemed to fall out of print and vanish all too swiftly from the shelves. The early 1980s was still a time when, for me, the aspiration to become a Scottish writer seemed as likely to be fulfilled as an earlier ambition of mine to become an astronaut.

It was also a time when after Fergus Lamont in 1979, Robin Jenkins found it impossible to get his new novels satisfactorily published in Scotland. I can only presume he was being offered such very small payments, if any, that he was convinced his novels could never be properly distributed. Hence one of Scotland’s leading novelists was finally denied both a wage and an outlet for his work in his own country. This is still not an extinct phenomenon. However, Robin Jenkins continued writing during those years. He truly became an autonomous author. It is well known that he accumulated a whole series of novel manuscripts, including The Awakening of George Darroch and Poverty Castle during the late 1970s and into the mid-1980s. That former novel, with the noble assistance of Harry Reid, finally did find a publisher in 1984 and afterwards, through a variety of differing publishers, Robin Jenkins began to release a steady flowering of late novels right into his very old age. An interesting description of all this is given by Reid in the welcome republication of Jenkins’ bitterly funny 1954 ‘football’ novel, The Thistle and the Grail (Polygon).

*

The act of publication and the act of writing are completely separate actions. Often painfully so. Only modernity itself has fused them together in our minds. Though it should not be romanticised, it can still be overlooked that almost every novelist, with no guarantee of glory, has toiled away on their first manuscript as a pure act. Nobody asks for or pays for all these first novels to be written yet all of them still are. Jenkins was the same, even denied an outlet; the Sisyphean task continued and he worked upon these late manuscripts as he must have once worked in obscurity on his first novel.

These all-too-real circumstances are very apparent in the novel-within-a-novel structure of Poverty Castle, one of those late works, first published in 1991 when Jenkins was approaching the age of eighty. Although the majority of the narrative concerns the middle-class and now wealthy Sempill family and the plot later veers to take in their nemesis figure – working-class student Peggy Gilchrist – the abiding presence in the novel is the figure of the elderly Argyllshire novelist, Donald, writing in the twilight of his days what may be his last novel. Unsurprisingly, Donald seems a closely autobiographical figure. Like Jenkins’, his work is neglected in Scotland. A native of Kilmory, near Tarbert – Jenkins was from Lanarkshire though long resident in Argyll – Donald is of ages with Jenkins and, like the real author did, lives near Dunoon in South Cowal, complete with the intimidating, diurnal passages of nuclear submarines.

Always a powerfully moral writer, often not without a hint of Scottish Calvinism, Jenkins’ novels, like The Cone-gatherers, often concern the creation of, and then through human fallibility, the withering of an Eden. Poverty Castle enforces just such a theme. Those opening sentences set out a challenge which intrigues us:

He had always hoped that in his old age he would be able to write a novel that would be a celebration of goodness, without any need of irony. The characters in it would be happy because they deserved to be happy.

Novelist Donald does try to create happiness – a kind of familial Eden – for the Sempills, renovating their idyllic Argyllshire house. I am not giving too much away to hint that physical human frailty, madness, moral weakness and cruel class division begin to sour the apple for his characters.

In this way Poverty Castle, for all its ‘old-fashioned’ surfaces of style and the highlighting of the individual artist as tortured, misunderstood loner at odds with society, is also presciently postmodern in its canny foregrounding of textuality over story. In other words, we know we are reading a written, imaginative fabrication – in fact, we know we are reading a fabrication about writing a fabrication – but still we read on. As Donald’s wife admits to herself:

She was doing what she had vowed not to do. By showing interest in his characters she was giving life to them.

Thus, if sometimes the pretty Sempill daughters seem too much a construct of Jenkins’ or Donald’s imagination, it is we who are becoming the Greek chorus of disapproval which includes Donald’s own wife. We – the readers – are the furies trying to undermine the genuine and frankly good intentions of this novelist who wants his characters to be happy. We assist in the destruction of the idyll. And the final conclusion of Poverty Castle is all the more moving and powerful. Like that other great Argyllshire novel, Gillespie, by John MacDougall Hay, set in Tarbert, Poverty Castle takes a cautiously dim view of our humanity. Attempts at happiness do not write blank by any means.

Alan Warner

Seil Island, by Oban

HE HAD always hoped that in his old age he would be able to write a novel that would be a celebration of goodness, without any need of irony. The characters in it would be happy because they deserved to be happy. It must not shirk the ills that flesh was heir to nor shut its eyes to the horrors of his century, the bloodiest in the history of mankind. It would have to triumph over these and yet speak the truth. Since he would wish also to celebrate the beauty of the earth he would set his story in his native Highlands, close to the sea.

In his 73rd year, when his powers were beginning to fail, he realised it was then or never. From the point of view of the world’s condition the time would never be propitious. Fears of nuclear holocausts increased. Millions guzzled while millions starved. Everywhere truth was defiled, authority abused. Those shadows darkened every thinking person’s mind: he could not escape them. They would make it hard for his novel to succeed.

‘Impossible, I would say,’ said his wife Jessie, a frank and cheerful Glaswegian. ‘You’ve always been severe on your characters, Donald. I can’t see you changing now.’

They were sitting in deck-chairs on the grassy patch – it was too rough and sheep-trodden to be called a lawn – in front of their cottage overlooking the Firth of Clyde, about fifteen miles from the Holy Loch. It was a warm summer afternoon. Red Admiral butterflies fluttered in flocks from one buddleia bush to another. From the safety of rhododen

drons chaffinches mocked Harvey the white cat asleep in the shade. Making for the opening to the sea, between the Wee Cumbrae and Bute, slunk an American submarine, black and sinister, laden with missiles.

In his childhood, in the West Highland village of Kilmory, there had been black beetles of repulsive appearance to which he and his friends had attributed deadly powers. Whenever one was encountered everybody had to spit with revulsion and yet also with a kind of terrified reverence, to ward off its mysterious evil. When he had grown up he had learned that the creatures were harmless, but he remembered them whenever he saw one of those submarines.

Jessie noticed him turning away his head and pretending to spit. ‘See what I mean!’ she cried. ‘You can’t forget those awful things and you could never let your characters forget them either. So how could they be happy?’

‘Many people seem to be happy in spite of them.’

‘Like me, for instance? Like my friends? But Donald, if you put us in a book you’d make us pay for our happiness. You’d want to show that it was just our way of escaping from despair.’

He smiled. ‘Well, isn’t it? Country dancing while the world burns?’

‘It’s not burning yet and with a little luck might never burn. What’s wrong with being hopeful? You’ve always had too low an opinion of humanity, Donald: in your books anyway. I suppose there were reasons. An only child, brought up in that smallminded place by a dreary bigot of a father. I’m sorry to miscall the dead but that’s what he was. If your mother hadn’t died so young I’m sure your books would have had happier endings.’

He had been six when she had died.

‘Where would you set it? Not in Scotland surely.’

‘Why not in Scotland?’

‘But you think the Scots have lost faith in themselves, don’t you? “The only country in history that, offered a modest degree of self-government, refused it.” No inspiration to a novelist, therefore. The very opposite. A blight on his imagination. You’ve said it often, Donald.’

Poverty Castle

Poverty Castle