- Home

- John Robin Jenkins

Poverty Castle Page 4

Poverty Castle Read online

Page 4

‘I think I know what you mean, darling. Once the house has been restored it will be very safe and we shall all be very happy there, I am sure. Except that the dampness might be harmful to your father’s chest.’

‘Is there anything wrong with Papa’s chest?’ Sleepy though she was Diana managed to sound sceptical. She was indeed very like her grandmother.

‘You must have heard him coughing.’

‘We think he does it when he wants us to pay him attention.’

Yes, sometimes poor Edward, the only male in the family, felt left out. With God’s help that state of affairs would not last much longer.

‘Goodnight darling.’

With difficulty she refrained from rushing out of the room. It occurred to her that Edward might have fallen asleep.

She found him wide awake and naked, applying lotion to midge bites. One, in a very tender place, itched abominably.

‘Let me, my love.’ Kneeling, she dabbed with delicacy.

Later they made love. No contraceptive device was used. Her love for her husband, she thought, would never have been fully expressed until she had given him a son. Often, at the outset, he would remind her fondly that if she did get pregnant again it might be another girl. That consideration, it had seemed to her, had caused him not to try as hard as he might. But not tonight. To her joy he performed with frantic zeal. Who was to say that it did not pass through her mind that she owed it to a midge? Conceptions could result from brief and cursory copulations. Therefore this love-making, fervent and thorough, was bound to be rewarded with the gift of a son. She was not aware of how many times she thanked him. It was four.

Four

NEXT MORNING instead of blue skies and sunshine there were dark clouds and pouring rain. Undaunted the girls in their hats, oilskins, and Wellingtons, all pillar-box red, went off to feed swans in the harbour, with rolls bought in the baker’s. From the hotel Papa telephoned Mr Patterson and arranged an appointment at eleven.

The girls could not be persuaded to stay with the swans.

They insisted on accompanying him. Effie reminded him it had been voted on. Besides, said Jeanie, they had a right to have a say in where they lived. Other fathers would have told them not to be impertinent. Papa meekly acknowledged the justice of their claim.

Since it wasn’t far, they walked. Papa and Mama shared an umbrella.

They had to stop and let Rebecca look at some small dolls dressed as Highland dancers, in a shop window. She wanted to add one to her collection.

Papa could not help saying, ‘Made in Hong Kong, I’m afraid.’

‘We ought to buy half a dozen then,’ said Effie, ‘for the people in Hong Kong are very poor, aren’t they?’

‘Those who made those dolls are very poor, certainly.’

‘In Hong Kong do they sell Chinese dolls made in Scotland?’ asked Rowena.

‘I wouldn’t think so.’

‘Well, they should.’

‘Why don’t the Chinese make their own dolls and the Scottish people make theirs?’ asked Jeanie.

‘It’s a matter of international co-operation.’

Papa smiled at his rueful reflection in the glass. He was used to having his utterances subjected to this ingenuous but rigorous examination. He took it very well, just as he did Diana’s beating him at chess, the twins trouncing him at draughts and Rowena and Rebecca being twice as fast at doing jigsaws.

Beside his in the glass was Meg’s face, still as radiant as it had been that morning when she had told him she was sure she had conceived and the child was male. Her breasts, look, were triumphant.

Her desire for a son had become an obsession. God knew what would happen to her if she did not get her wish. Those absences of mind weren’t indications of mental derangement, the psychiatrist had said. But what if one day she never returned?

Meanwhile the girls were helping Rebecca to count her money. ‘I don’t think I’ve got enough,’ she said.

‘Papa will make it up,’ said Effie.

They all marched into the shop.

The shopkeeper, a small thin woman with spectacles, peered at them suspiciously. She had reason to believe that children in groups, with or without their parents, were likely shoplifters. That they were all well dressed and spoke politely did not necessarily mean that they were honest. She had read in the newspaper of titled ladies being caught shoplifting.

The youngest girl had to be lifted up to inspect the dolls set out on the counter.

‘Where were they made?’ asked one who looked like a twin.

‘In Scotland of course. These are genuine tartans.’

They all burst out laughing as if she’d made a joke.

‘You were wrong, Papa,’ cried the other twin.

He should have cuffed her ear. Instead he grinned sheepishly.

‘How much is this one, please?’ piped the youngest, whom they called Rebecca, a Jewish name surely.

‘Three pounds fifty-five pence. This kilt is real silk.’

She put what money she had on the counter. Her father made up the difference.

The doll was put in a box.

As they went out the shopkeeper, assuaged by her three hundred per cent profit, decided that they were what they appeared to be, a handsome, well-to-do, and highly respectable family.

Out on the pavement Effie said: ‘Did you see her looking at us as if we were thieves?’

‘You mustn’t say things like that, Effie,’ said Mama.

Rowena took something from her pocket. It was a tiny white glass cat with green eyes.

‘Where did you get that?’ asked Diana.

‘I took it.’

They were all shocked. They stopped.

‘Rowena Sempill, you didn’t!’ cried Jeanie.

‘I did.’

Papa and Mama stared at each other, appalled. A serpent had crept into their Eden.

‘Good heavens, Rowena,’ said Mama, ‘do you know what you are saying?’

Rowena smiled. ‘When she wasn’t looking I took it.’

‘But you had just to ask and I would have bought it for you,’ said Papa.

‘She’ll have to take it back,’ said Effie.

Rowena looked pleased at this suggestion.

At any moment, thought Papa, the shopkeeper and a policeman would come running towards them. The cat couldn’t cost more than two pounds. He’d offer twenty to have the matter hushed up. Poor Rowena after all was only seven. She would have to be taken to a child psychologist.

‘Say you took it by mistake,’ said Jeanie.

Rowena shook her head. ‘I wanted to take it.’

‘Good God,’ muttered Papa, as if she’d confessed to murder.

‘In heaven’s name, why, my pet?’ asked Mama.

‘I know why,’ said Diana, calmly. ‘She was pretending to be a shoplifter. She’s always pretending to be different things.’

The twins confirmed it. ‘She likes to act,’ said Effie.

‘Will I take it back now?’ asked Rowena. She was looking forward to the part of playing the penitent thief.

Papa thought: I don’t know my children. Would I, if they were boys?

Mama thought: Don’t they say a child does naughty things as a signal that she is not being given enough love? But I love all my children, and of them all Rowena is the one who seems to want or need it least.

‘I suppose I must take it back and explain,’ said Papa.

‘I shall come with you,’ said Mama.

‘I’d better go,’ said Diana.

The twins nodded. They were sure Diana would handle it better than Papa.

‘Give me money, Papa,’ she said.

He gave her a five-pound note. ‘What will you say?’

‘I’ll say she’s just seven and forgot to pay.’

Rebecca, in tears, was comforting Rowena, who was dry-eyed and still smiling.

‘She’ll ask if Rowena took other things as well,’ said Effie.

That hadn’t occ

urred to Papa. ‘Did you, my pet?’

‘Of course she didn’t,’ said Diana. ‘She just needed to take one thing for her game. That’s all it was, just a game.’

‘Not a very nice game,’ murmured Mama.

With the glass cat in her fist Diana marched back to the shop. She didn’t hurry, but it wasn’t because she was afraid. For her family’s sake she would have faced a tiger.

They huddled under an awning outside a grocer’s. Luckily it was still raining and few people were about.

Can it be, wondered Papa miserably, that my poor wee daughter is mentally retarded? Have we been so proud of her beauty that we haven’t noticed the dimness of her mind?

Guiltily he glanced at Rowena. She was looking at him with eyes as bright and intelligent as they were beautiful.

‘I’m sorry, Papa,’ she said. ‘It was silly.’

‘She’s still acting,’ muttered Effie to Jeanie. ‘Sometimes she doesn’t know whether she’s acting or not.’

They saw Diana come out of the shop, holding her head high.

The twins ran to meet her. ‘What did she say? Is she going to tell the police?’

Diana did not speak until they had joined the others. ‘It’s all right. She said anybody could make a mistake.’

‘That was generous of her,’ said Papa. ‘Did she take the money?’

‘Yes. She said it was three pounds forty pence. It shouldn’t have been. I saw the price on one the very same: it was only two pounds eighty pence.’

‘Maybe it was a smaller one that was two pounds eighty pence,’ said Jeanie.

‘The one I took was the smallest,’ said Rowena, still unperturbed.

‘We are living in a dangerous world,’ muttered Papa.

It was now ten past eleven on the church clock.

‘We are late for our appointment, Papa,’ said Diana.

‘Should we keep it, my dear? Do we want to live anywhere near here?’

‘In Kilcalmonell, in that old house, when it is repaired, we shall be safe.’

With that defiant prophecy she walked across the road, threw the glass cat into the harbour, and then led the way to the lawyer’s office.

Effie and Jeanie nodded. What could be safer, as far as collapsing floors and falling slates were concerned, than a house newly rebuilt?

They frowned too. What other dangers had Diana meant, and Papa too, and Mama as well, judging by her frightened eyes?

Five

MR PATTERSON was reading the financial columns of the Glasgow Herald when Miss McGibbon, his white-haired clerkess, came to announce that Mr and Mrs Sempill had arrived for their appointment.

‘Nearly fifteen minutes late,’ she said, grimly. ‘They’re gentry, or think they are. Scotch gentry,’ she added, with a touch of scorn.

Mr Patterson smiled. Peggy – though he would never have dared to call her that, since she was a prudish old spinster – lacked humour and tolerance, unlike himself who had perhaps too much for a man in his profession.

‘Have they come about a house?’ she asked.

‘I believe so.’

‘Which one?’

‘He didn’t say.’

‘It’ll have to be a big one. I can’t see her living in a three-bedroomed bungalow.’

Mr Patterson folded the newspaper and put it away in a drawer. From another drawer he took out an important-looking document and placed it in front of him.

‘You can show them in now, Miss McGibbon.’

‘All of them?’

‘How many are there?’

‘Seven. There are five girls. Two look like twins.’

‘Good heavens!’

‘Dripping all over the place.’

‘Well, it’s a wet morning. Perhaps you and Mary could entertain the children while I talk to their parents.’

‘How are we to do that?’

‘Give them magazines to look at.’

‘We have none suitable for children of their age.’

‘Send them next door to Farino’s for wafers. Take it out of the petty cash.’

‘I’ll let Mary deal with them. She’s nearer their age.’

But when she returned to the outer office and said that Mr Patterson was now ready to see Mr and Mrs Sempill the five Misses Sempill made it plain that they were not going to be left behind. They did it politely but firmly. Miss McGibbon happened to believe that modern children were horribly spoiled. Now she saw that the gentry were no exceptions.

‘You promised, Papa,’ said one of the twins.

‘We voted,’ said the other.

‘But Effie, my dear, it might not be convenient for Mr Patterson to have so many people in his office.’

‘There wouldn’t be enough chairs,’ said Miss McGibbon.

‘We’ll stand,’ said the oldest girl, with what child-lovers would have called dignity but to Miss McGibbon was downright impudence.

It was their mother’s fault: a vague creature who scarcely knew what day of the week it was. Her yellow raincoat with hat to match must have cost at least a hundred pounds, yet the one was stained with what looked like oil and bramble juice, while the other had been pulled on any old way. Or was that straggling out of her hair deliberate, to show off its golden colour and to hint at its abundance? Just as the raincoat was open, revealing a white jumper of finest cashmere and white-and-green skirt of top-quality tweed, not to mention immodestly prominent breasts. Her jewellery might be genuine but there was too much of it. She was the kind of woman that Miss McGibbon and her friend Mary McGill, schoolmistress at Kilcalmonell, over their drams, called a Delilah. If men pinched her bottom she would not resent it as a decent woman should but would regard it as a tribute.

Her husband was hardly a Samson: he was tragic in quite a different way. Like Bonnie Prince Charlie, after the Battle of Culloden. His manners indeed were royal. Miss McGibbon couldn’t imagine him being rude or coarse or unkind. She had no hesitation in putting him on the list (not even God or Mary McGill knew of it) of men she would have welcomed into her bed. Some had won the honour because of their hairy-chested virility, others for their red-eyed passion, but Mr Sempill deserved it for his gentleness. That he was twenty years or more younger than she did not matter: in her dreams she was ageless, like Cleopatra.

Mr Patterson was displeased when not only Mr and Mrs Sempill but their five children too were ushered into his office.

His displeasure lasted only for moments. The five little girls in their red raincoats and with their alert eyes reminded him of robins. He had three granddaughters but he had to confess they had never lifted his heart as high as these Sempill girls did.

Their mother had his heart somersaulting. She was tall. (His Bessie was only five-feet-two.) Elegant. (Bessie was sturdy.) Her large blue eyes were soft with trust and innocence. (Bessie’s were blue also but hard with scepticism.) She had a fine figure. (Bessie’s stomach was large.) Her hair was fair and lustrous. (Bessie’s was grey, stiff, and growing scarce.) If she had a fault it was that she doted on her wishy-washy husband, but as an elder of the Church of Scotland Mr Patterson should not have seen that as a fault but rather as another virtue.

The parents sat on the other side of the big desk. The girls stood in the background, in a row. They had taken their hats off. The eldest, the only dark-haired one in the family, looked more businesslike than her father.

‘Now, Mr Sempill, what can I do for you?’

‘Yesterday, Mr Patterson, visiting Kilcalmonell, we came upon a house that took our fancy. We were informed that you were the person to consult. It is close to the beach. It has not been occupied for many years. It is therefore in a ruinous condition. As a consequence it is known locally as “Poverty Castle”. I am by profession an architect, Mr Patterson, and it seemed to me a pity that a house which at one time must have had character should have been allowed to become a ruin.’

Mr Patterson was astonished but was too wily to show it. Calmly he took a file from a cabinet. Its most recent a

dditions were letters from Mr Wrigley-Thomson, nephew and heir of Mrs Braidlaw. For over thirty years she had refused to let Ardmore be sold or rented or kept weatherproof. Mr Wrigley-Thomson on the contrary was desperate to be rid of it. He had discovered that substantial rates were still having to be paid.

‘The house you are referring to, Mr Sempill, is Ardmore. Is not your description of it as a ruin somewhat extreme?’

The girls spoke up, one after the other.

‘It’s got lots of slates off the roof.’

‘It lets in rain in lots of places.’

‘Some of the ceilings are on the floors.’

‘It’s got no back door.’

‘Sheep and cows get in. Their dirt’s everywhere.’

‘Rebecca slid on a cow-pat.’

‘There are millions of cobwebs.’

Well-rehearsed wee lassies, thought the lawyer. Then he saw that he was being unfair. They had spoken for themselves. They always would.

‘If you are interested in purchasing a property in the district, Mr Sempill, I have a number for sale, in what is known as “walk-in” condition.’

‘We are interested in this one. I understand it was owned by an old lady recently deceased. Who is the present owner?’

‘Her nephew. He lives in Putney.’

‘Is he prepared to sell it?’

‘He may well be.’

‘How much does he want for it?’

That was how gentry did business: brutally to the point. Mr Patterson had had working-class clients who had shrunk from mentioning money, thinking it would be bad manners.

The girls were gazing at him like judges. They expected fair play.

‘There is a complication, Mr Sempill. Ardmore was once part of Kilcalmonell estate. It was built for the mother of a past laird, before the family became impoverished. Indeed the whole estate passed out of the hands of Kilcalmonell Campbells years ago and is now in the possession of an English gentleman, Sir Edwin Campton. Sir Edwin wishes to buy Ardmore, to raze it to the ground. He believes it detracts from his privacy. Mrs Braidlaw refused to sell. Her nephew, as I have said, sees it differently. However, he considers that the offer made on Sir Edwin’s behalf is unacceptably low.’

‘Whatever it is,’ said Mr Sempill, ‘I shall double.’

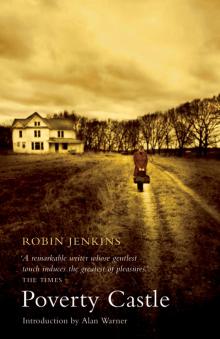

Poverty Castle

Poverty Castle